By Gemma Rosenthall, Loyola University Chicago

“I have found my one talent,” Bertha Honoré Palmer (1849-1918) revealed during a 1911 interview given from her coastal estate, “it is to watch beautiful things grow and see flowers blossom as I plant them.” A reporter traveled to interview the city’s prized socialite whose new environs led her to conclude, “the most wonderful thing in the world is a garden.” After years of civic work in Chicago, Palmer became a celebrity once again—this time for stewarding 200,000 acres of land in Sarasota Bay, Florida. [1]

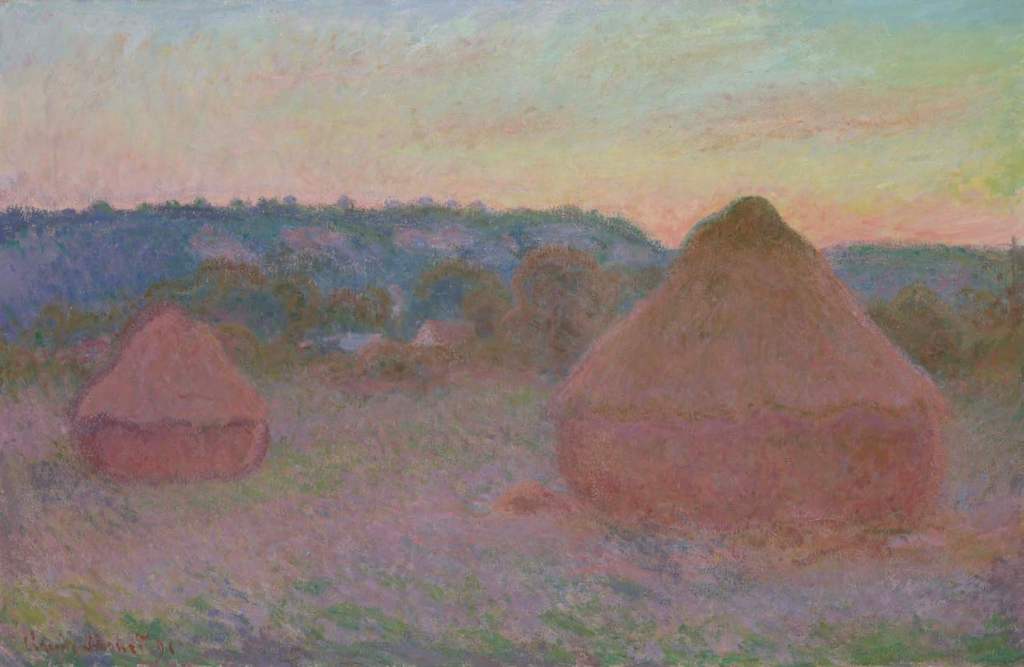

What of the reformer whose largesse gave shape to Chicago’s Art Institute? How does a shine for lilacs figure into her legacy? It figures intuitively if we take Palmer’s patronage of Impressionist artwork as a connection between her life as Chicago’s Gilded Age progressive and Florida’s blithe romantic. In each case, her conception of beauty and clarity of mind produced momentous results.

Palmer was attracted to Impressionism despite its rejection from the contemporary canon and was no more curtailed by the 19th century’s standards for art than she was by its roles for women. Far from content in the shadow of domestic life, Palmer forged a career in business and progressive causes. She wielded a degree of influence over the emerging city that rivaled her husband’s, the real estate magnate Potter Palmer. In the decade she spent in Florida following Potter’s death, Palmer doubled his fortune. [2]

Transgressive as her lifestyle might have been, she did not depart from the norms of her world entirely. Impressionism was unorthodox, but it was French unorthodoxy, and Midwestern elites swore fealty to French aesthetics. [4] To Palmer’s credit, her defense of Impressionism rested on its capacity to express, not its French origins: “Impressionism is only direct sensation,” she told the more conservative guests who observed the growing array of paintings that decorated her lakefront mansion. [1] Evidently, her sensibilities were not controversial enough to disrupt her social standing. She could hardly have been a radical and the darling of Midwestern society, or in the precise terms of the press, “the princess of the prairie.” [2]

Palmer was so absorbed with her paintings that she was rumored to sleep with several under her bed; teeming green vistas that foretold the land she would steward. Renoir’s Acrobats at the Cirque Fernando went with her wherever she traveled. [2] These anecdotes risk framing her collection as the fancy of a moneyed eccentric. As with all her exploits, she was moved by an equal measure of artistic inspiration and financial discretion. She worked closely with a network of Impressionists to cull a representative sample of the form, which included ninety works by Monet. While Palmer kept many of these for herself, her business savvy compelled her to sell several items so that her collection could turn a profit. She would leave a robust personal collection to the Art Institute of Chicago in her will. [5]

Convinced of the edifying effect of art upon the public, Palmer made herself indispensable to preserving the Art Institute, which had been built as a part of the World’s fair. It risked collapse as money from the fair dried up. It is largely owing to Palmer’s personal contributions and those she solicited from her friends that the museum became a fixture of Chicago’s landscape. [6]

Beauty, for Palmer, was clearly neither a superficial nor a recreational concern, but a material one. Perhaps she found this principle articulated in Impressionism, which transforms the motion of quotidian people and places into occasions worthy of focus. Palmer imagined imbuing purpose onto her city as the impressionists did onto their subjects.

More than a century later, her donated Renoirs, Monets, and Pissarro’s remain prominently displayed in a museum Chicagoans can visit Thursdays free of charge. [5] On a tour led by the Art Institute’s president, a visitor guessed that the museum had spent profligately on its sweeping Impressionist exhibit. “Not at all,” the president said. “In Chicago we don’t buy Renoirs. We inherit them from our grandmothers.” [4] Palmer, by this logic, is the giant of Chicago grandmothers.

Her values and tastes are not only remembered here. The expert treatment of the Sarasota Bay property permanently changed the course of land use in the wider region. She began, for example, a successful program to eradicate Texas fever tick among local cattle. She kept close contact with the FDA to receive notice when foreign plants were imported, and effectively integrated many into her estate’s ecosystem. Chayote, a type of squash, was among these species. [7] Owning land naturally inspires a vision for its use, but only a vision of design and industry as advanced as Palmer’s could have wrought this progress.

In 1915, a reporter wryly juxtaposed Palmer’s early accomplishments with her present role as “the world’s most renowned market gardener.” [1] Palmer rejected the idea that a gulf separated the energies she devoted to Chicago and Sarasota Bay. She was a woman who acted upon her corner of the world, wherever that happened to be. When she conveyed a humble appreciation of her 200,000 acre “garden” in the 1911 interview, she elevated her agricultural career to the status of her civic career.

Palmer’s semi-retirement among brilliant flowers seemed inane to the 1915 reporter who understood her to be someone else. But he had missed the point. How else would a wealthy patron of the avant garde—known once to the Midwest as princess—spend her final years than if in a garden of her own design? If Palmer’s one talent was to watch beautiful things grow, it was by her hand that they grew—cultural institutions and coastal squash alike.

[1] Peters Smith, Barbara. “From White City to Green Acres: Bertha Palmer and the Gendering of Space in the Gilded Age.” USF Tampa Graduate Theses and Dissertations, Digital Commons @ University of South Florida, 2015. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6973&context=etd

[2] Dellos, Amelia, dir. Love Under Fire: The Story of Bertha and Potter Palmer. 2013; Chicago, Illinois; Corn Bred Films.

[3] Palmer, Bertha. “Address Delivered By Mrs. Potter Palmer, President Of The Board of Lady Managers, On The Occasion Of The Opening Of The Woman’s Building.” Chicago, Illinois, 1893.

[4] Bernstein Saarinen, Aline. The Proud Possessors: The Lives, Times, and Tastes of Some Adventurous American Art Collectors. New York: Randomhouse, 1958.

[5] The Art Institute of Chicago. “Pissarro Paintings and Works on Paper at the Art Institute of Chicago.”

https://publications.artic.edu/pissarro/api/epub/7/955/print_view

[6] Sexton Kalmbach, Sally. The Jewel of the Gold Coast: Mrs. Potter Palmer’s Chicago. Chicago, Illinois: Ampersand, Inc, 2009.

[7] Sarasota County History Center. “Mrs. Bertha Palmer’s Vision.”

http://www.sarasotahistoryalive.com/index.php?src=directory&srctype=detail&refno=1531&cate

gory=People&view=history

Leave a comment