Following the nationwide protests over the past few years’ racial and police reforms, significant monuments’ relevance and suitability have come into question. Statues and monuments have been toppled and torn down, scrutinized and reviewed, and new ones erected in an attempt to capture our current culture. One might reasonably ask where we draw the line. The surface-level question, “how do we strike the balance between removing disconcerting monuments and preserving a trace of them” comes to the forefront, but there is a deeper underlying cultural-historical balance that needs to be addressed. How do we compromise the commemoration and preservation of our historical lessons with the current public perception of monuments and the present cultural values?

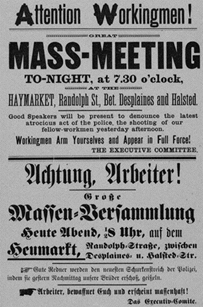

On May 30, 1889, a commemorative nine-foot bronze statue depicting a Chicago policeman was unveiled to honor the policemen’s sacrifice who lost their lives the night of the 1886 Haymarket Affair. What started as a peaceful protest the evening of May 4, 1886, transformed into chaotic violence. Workingmen met for a rally in response to the striking of workers at the McCormick Harvester Works, creating a platform to advocate for labor rights. Although intended as a peaceful demonstration, flyers advertising the gathering were dispersed with the line, “Workingmen arm yourselves and appear in full force” [1]. Towards the end of the Haymarket Square rally, a group of policemen advanced to disperse the crowd and were attacked by an explosive thrown by an unidentified individual. The police opened fire, and chaos ensued; seven police officers, and at least one civilian, were killed, and many more were injured [2].

Three years following the riot, the Haymarket statue of the policeman was commissioned and installed. Funded by the private funds raised by the Union League Club of Chicago, the statue was designed by Frank Batchelder and sculpted by Johannes Gelert [3]. The statue would become the first known monument in the United States honoring police officers [4] and has been moved seven times. Much like the statue’s commemorative inspiration, its history is one of violence.

The original Haymarket statue was placed in the middle of Randolph Street on a marble pedestal engraved with the last command of Captain William Ward delivered in the Haymarket riot. “In the name of the People of Illinois, I command peace” [5]. However, due to vandalism and interference with traffic flow, the statue was moved for the first time to Randolph Street and Ogden Avenue near Union Park. In 1903, the seals located on the statue’s pedestal were stolen and had to be replaced.

On the 41st anniversary of the Haymarket Affair, a streetcar, driven by William Schultz, jumped its tracks and crashed into the statue’s pedestal, causing the figure to fall off the base. The city had the statue restored and moved to Union Park. The statues’ third move was in 1957 due to the Kennedy Expressway’s construction, causing the placement of the statue to be moved to Randolph Street and the Kennedy Expressway. On the 82nd anniversary of the riot, the monument was vandalized with black paint, and soon following this event, the statue was destroyed by an explosive placed in between the legs of the figure in 1969.

The first explosion, which may have been a symbolic reenactment of the original Haymarket protest, was credited towards Weather Underground members, otherwise known as Weatherman, who had had other altercations with the police throughout Chicago [6]. The statue was rebuilt and replaced in May of 1970 but was blown up again in October of the same year. After the second explosion, an individual called several news outlets to declare that the Weatherman did the bombing to “Show our allegiance to our brothers in New York prisons and our black brothers everywhere. This is another phase of our revolution to overthrow our racist and fascist society. Power to the People” [7].

Despite these attacks on the Haymarket monument, the city continued to take care of the statue. It had the statue repaired again and was moved to the State Street Chicago Police Headquarters Building in 1972 [8]. For over four years, the statue remained there before being relocated to the courtyard at the Chicago Police Training Academy. However, the statue did not stay at this location and was rededicated to its final (current) destination. In 2007 the statue was rededicated at Chicago Police Headquarters and placed on a new pedestal where it remains presently.

As the turbulent history of this one monument demonstrates, no monument is a neutral marker of an event; the interpretation of the artist and intent of the commissioning source, as well as prevailing public sentiment, shape the ultimate product. It would be naïve to claim monuments, such as the Haymarket statue, are only about the “past”; they are politically potent in the present. The concerns and views of the times are continually applied as a litmus test of public acceptability. It is our responsibility as a society to ensure we balance the historical significance and our shared cultural journey with the intended commemoration and conception. In many cases, this could be accomplished through the introduction of additional contextual information surrounding the monument, providing that bridge between contemporary social norms and mores to the period in which the monument was erected. The Haymarket monument represents and commemorates the lives of the policemen lost during the Haymarket Affair; perhaps, some of its tumult of being rebuilt, removed, and rededicated could have been avoided if a more balanced presentation had been offered. The monument does have the benefits of preserving both the art and the historical bearing and should be weighed in a careful manner so that we do not regret the loss of critical journey markers of our spurtive societal growth. This is not to say that some monuments have outlasted their relevance, and need to be updated or replaced. But given the highly charged political and emotional atmosphere of this year, we need to entertain a more considered approach when we contemplate removing historical monuments.

Isabelle Sapienza, Loyola University Chicago

[1] Flyer advertising Haymarket Rally, Printed at the Office of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, 1886.

[2] Brian Duignon, “Haymarket Affair; Unites States Hstory, 1886”, https://www.britannica.com/event/Haymarket-Affair

[3] Wendy Koenig, “The Police Monument”, Chicago Public Art, http://chicagopublicart.blogspot.com/2013/09/the-police-monument-haymarket-riot.html

[4] “Haymarket Memorial Statue”, https://www.chicagocop.com/history/memorials-monuments/haymarket-memorial-statue/

[5] Ibid.

[6] Richard M. Sommer, “Dyn-o-Mite Fiends; The Weather Underground at Chicago’s Haymarket”, January 10, 2008.

[7] John Kifner, “Ominous Threat in Attacks on the Police,” New York Times, September 6, 1970.

[8] “Haymarket Statue Moved” Chicago Police Star Magazine, March, 1972, retrieved from ChicagoCop.com.