by Mary Cole Daulton, Loyola University Chicago

Around the country, monuments have come into sharp focus in recent years due to a shifting ideology on memory and history. The gender gap and racial gap have become an important part of the overall monument discussion. In the Near West Side neighborhood of Chicago, there stands a monument to a 19th century Native American war chief. Seemingly, this representation of an important leader to a minority group should be a good thing. But this isn’t a monument to a noble Sauk leader – instead, this likeness is used to represent the Chicago Blackhawks hockey team. How, then, do we view the legacy of Chief Black Hawk? How can a monument to a man not be for the man himself? Ultimately, who owns his narrative – his tribe or the hockey team?

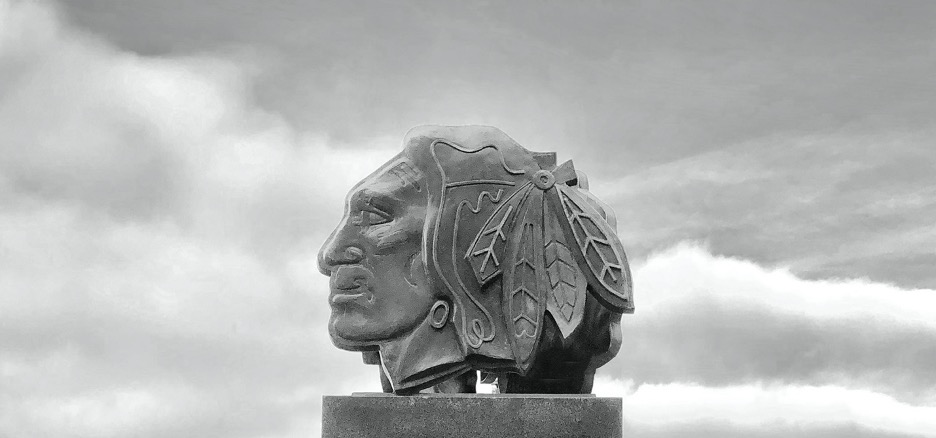

The monument’s inception was to honor a long history of hockey in the city of Chicago. It was erected in October of 2000 to commemorate the 75th anniversary season of the Blackhawks hockey club [4]. Erik Blome, a Chicago native, was commissioned by the team to create the monument of the Chicago Blackhawks logo, colloquially known as the “Indian head” and also acknowledged to represent Chief Black Hawk [5]. The intention of the monument is not related to the Native American profile that towers over the bronze hockey player. But that alone requires answering: why is it so easy to overlook the part of the monument that depicts a real, historic Native American chief? Because to most people, it is merely a hockey logo.

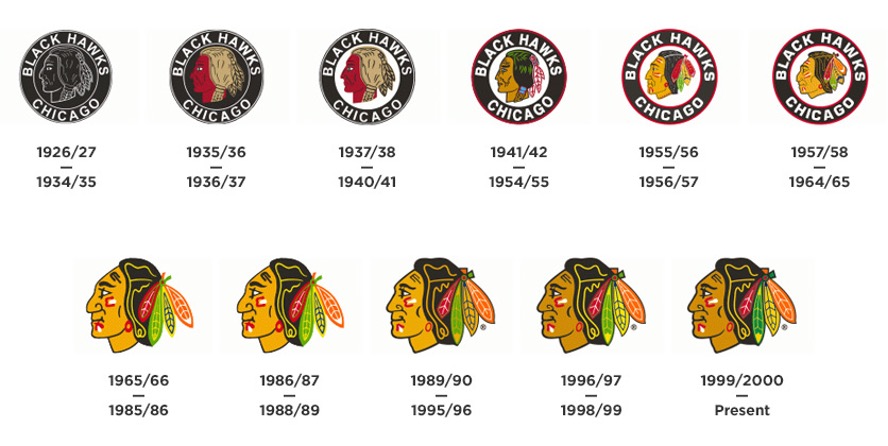

When discussing the logo, many believe the Blackhawks usage has always been respectful, while other sport teams have failed in that regard. In a 2014 article hailing the logo’s unique nature, the author wrote, “The Blackhawks have never indulged in the kind of cartoonish portrayal of Native Americans we’ve seen in other sports” [6]. The Blackhawks have used an iteration of this logo since their inception in 1926, and it has always featured a drawing or illustration of Chief Black Hawk’s profile. Where is the line between a caricature and a cartoon?

The hockey club boasts that its logo is often voted “the best logo in the history of professional sports” [8]. In a 2008 poll that voted the Blackhawks logo as the “best”, Ryan Kennedy wrote the team’s logo “represents everything this competition is about. It is instantly recognizable, has universal appeal and has inspired countless imitations. The logo itself has an unwavering sense of pride and duty to it and looks great on a jersey or a hat. It is truly one of the classics in all of sport” [9]. At no point does Kennedy acknowledge the logo is special because of its connection to Chief Black Hawk; his primary concern was instant recognition and the selling of merchandise.

Many believe the hockey team has not received as much pressure or vitriol due to the respect they show their logo and active participation with Native Americans in Illinois. However, the schism in the Native American community regarding the hockey club’s logo is well documented. Some believe it is an opportunity to educate the public, while others believe there can be no exemption for a racially motivated logo regardless of how team handles its public outreach. Studies have shown the ill-effects that Native American mascots and logos can have on indigenous people. Dr. Arianne Eason of UC Berkeley wrote, “Regardless of what sports fans claim, the outcomes are clear, Native mascots harm and offend Native people, especially highly identified Native people” [10]. Heather Miller, the executive director of the American Indian Center in Chicago and a member of the Wyandotte Nation, is actively against any sports team using Native American names and imagery. The AIC cut ties with the Blackhawks a few years ago, and Miller does not anticipate a reconciliation anytime soon. Miller believes it is entirely hypocritical because as teams were being named after Native American legends, Native American people were massively suffering, on reservations or in cities, even Chicago. She continued, “Our children were being systematically removed from reservations and forced into boarding schools, forced to cut their hair, forced to not learn their language or speak their language, so our culture was being erased. And yet their sports teams and their universities were putting these depictions and images of us in place, saying that this was how we behaved.” [11]. Further, the National Congress of American Indians has spoken about the psychological consequences of using native mascots. They clearly state that the intolerance born in “Indian” sports mascots creates alarmingly high rates of hate crimes against native people. “Specifically, rather than honoring Native peoples, these caricatures and stereotypes are harmful, perpetuate negative stereotypes of America’s first peoples, and contribute to a disregard for the personhood of Native peoples.” [12]. While the NCAI has not spoken for or against the Blackhawks hockey team, they do reference the National Hockey League in their policy on “Professional Sports and Harmful Mascots” [13].

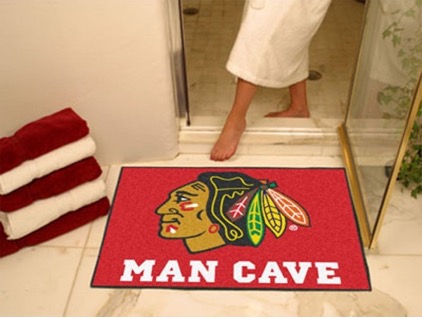

In 2010, Joe Podlasek gave an interview on the topic of the Blackhawks logo. Podlasek is the CEO of Trickster Cultural Center and has worked with the Blackhawks organization in the past [14]. In the center of the locker room, there is a large rug with the logo on it that superstition says players are not allowed to step on. Some call this superstition “respecting the logo”. Podlasek said, “For us, that’s one of our grandfathers. Would you do that with your grandfather’s picture? Take it and throw it on a rug? Walk on it and dance on it?” [15].

The organization actively celebrates Native American Awareness month on social media, but the awareness and promotion do not solve the issue of their branding and how it devalues Chief Black Hawk. Podlasek specifically informed the organization that they needed to do a better job educating their fans about how disrespectful wearing Native American traditional headdresses to the games was [18]. This summer, the team took the positive step of banning costume headdresses from team-sanctioned events, including home games. The statement put out by the organization specifically mentions “conversations with our Native American partners”, and how the headdresses “are sacred, traditionally reserved for leaders who have earned a place of great respect in their Tribe and should not be generalized or used as a costume or for everyday wear” [19]. While this is one step in the right direction, the thoughts and meaning behind it show incredible promise. The same mentality of establishing respect needs to now be applied to their logo.

In July of 2020, amid racial equality demonstrations after the murder of George Floyd, many called on the hockey club again to commit to changing its name. The Blackhawks responded by defending their logo and issuing the following official statement:

The Chicago Blackhawks name and logo symbolizes an important and historic person, Black Hawk of Illinois’ Sac & Fox Nation, whose leadership and life has inspired generations of Native Americans, veterans and the public. We celebrate Black Hawk’s legacy by offering ongoing reverent examples of Native American culture, traditions and contributions, providing a platform for genuine dialogue with local and national Native American groups [20].

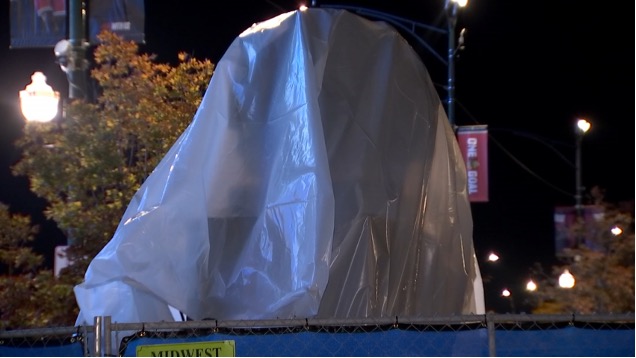

In response, on Columbus Day, or Indigenous Peoples Day, the Blackhawk statue was vandalized. Red paint was thrown on the logo and graffiti on the concrete around the statue read, “Land Back”, and “take your trash with you”. The first photos of the vandalism were posted on Twitter by an account called @zhigaagoong [21], which is a Native American phrase for the land of Chicago. The statue of the logo, the monument to Chief Black Hawk, was covered with a tarp, fenced for safety, and subsequently sent for repairs [22].

The team plans to keep the name because it believes the name honors Chief Black Hawk. How can a commercialized logo represent a real-life man? With every t-shirt, novelty license plate, or dog leash manufactured, the story of Chief Black Hawk gets smaller and the narrative of Chief Black Hawk continues to be taken away from his tribe and his people. The name of the team may have been intended to honor Chief Black Hawk, but once his likeness was commercialized, the amount of respect diminishes. As people walk by the Blackhawks statue outside the United Center, they don’t see a monument to Sauk hero. They see a statue to a team they paid money to see play a game. The profile of Chief Black Hawk doesn’t represent the Sauk tribe anymore. It’s permanently attached to a hockey team with its own unique story. Commercializing a historic figure’s memory has devalued the lessons and the history surrounding Chief Black Hawk. While once an honorary recognition, the business using Chief Black Hawk’s name and likeness has usurped his narrative that rightly belongs to the Native American people.

Mary Cole D

[1] Photo licensing purchased by Mary Cole Daulton, taken by Jim Roberts, December 22, 2018.

[2] Photo licensing purchased by Mary Cole Daulton, taken by Jim Roberts, December 22, 2018.

[3] Photo credit to Erik Blome, https://www.erikblome.com/united-center-blackhawks.

[4] “Chicago Blackhawks 75th Anniversary Commemorative Monument,” Chicago Public Art, accessed November 16, 2020, http://chicagopublicart.blogspot.com/2013/08/chicago-blackhawks-75th-anniversary.html.

[5] Erik Blome, “Chicago Blackhawks 75th Anniversary Monument,” Erik Blome–Sculptor, accessed November 16, 2020, https://www.erikblome.com/united-center-blackhawks.

[6] Adam Proteau, “NFL’s ‘Redskins’ days are numbered – are the NHL’s Blackhawks next?,” SI: The Hockey News, June 18, 2014, https://www.si.com/hockey/news/nfls-redskins-days-are-numbered-are-the-nhls-blackhawks-next.

[7] Copyright “History Of The Chicago Blackhawks”, accessed November 16, 2020, https://tbanyan.neocities.org/html.html.

[8] Brad Boron/Chicago Blackhawks, “THN ranks Blackhawks logo tops in the NHL,” NHL.com, August 24, 2014, https://www.nhl.com/blackhawks/news/thn-ranks-blackhawks-logo-tops-in-the-nhl/c-31173.

[9] Chicago Blackhawks Press Release/Chicago Blackhawks, “Blackhawks Logo Voted #1 in NHL,” NHL.com, accessed November 16, 2020, https://www.nhl.com/blackhawks/news/blackhawks-logo-voted-1-in-nhl/c-476429.

[10] “Offensive to Native Americans, Racist Mascots Have No Place in Sports,” Cision: PR Newswire, accessed November 16, 2020, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/offensive-to-native-americans-racist-mascots-have-no-place-in-sports-301003720.html.

[11] Scott Powers, “Is it time for the Chicago Blackhawks to drop their Native American logo?,” The Athletic, June 25, 2020, https://theathletic.com/1888307/2020/06/25/is-it-time-for-the-chicago-blackhawks-to-drop-their-native-american-logo/.

[12] “Ending the Era of Harmful ‘Indian’ Mascots,” NCAI Policy Research Center, accessed November 23, 2020, https://www.ncai.org/proudtobe.

[13] National Congress of American Indians, “Ending the Legacy of Racism in Sports & The Era of Harmful ‘Indian’ Sports Mascots,” October 2013, https://www.ncai.org/attachments/PolicyPaper_mijApMoUWDbjqFtjAYzQWlqLdrwZvsYfakBwTHpMATcOroYolpN_NCAI_Harmful_Mascots_Report_Ending_the_Legacy_of_Racism_10_2013.pdf.

[14] Scott Powers, “Is it time for the Chicago Blackhawks to drop their Native American logo?,” The Athletic, June 25, 2020, https://theathletic.com/1888307/2020/06/25/is-it-time-for-the-chicago-blackhawks-to-drop-their-native-american-logo/.

[15] “Native-Americans weigh in on “Blackhawks” name,” ABC7, accessed November 16, 2020, https://abc7chicago.com/archive/7479527/.

[16] “Indoor Rug” sold at Rally House, a merchandise partner with the Chicago Blackhawks, https://www.rallyhouse.com/chicago-blackhawks-34×45-all-star-interior-rug-1654475.

[17] Copyright Getty Images, taken by Scott Olson, 2015, https://www.gettyimages.co.nz/detail/news-photo/fans-wait-for-the-start-of-a-parade-to-celebrate-the-news-photo/477600560?adppopup=true.

[18] Scott Powers, “Is it time for the Chicago Blackhawks to drop their Native American logo?,” The Athletic, June 25, 2020, https://theathletic.com/1888307/2020/06/25/is-it-time-for-the-chicago-blackhawks-to-drop-their-native-american-logo/.

[19] Chicago Blackhawks/Blackhawks.com, “A Note to Our Blackhawks Community,” NHL.com, accessed November 23, 2020, https://www.nhl.com/blackhawks/news/a-note-to-our-blackhawks-community/c-317689134.

[20] Chicago Blackhawks/Blackhawks.com, “STATEMENT: Blackhawks Statement on Name and Logo,” NHL.com, accessed November 16, 2020, https://www.nhl.com/blackhawks/news/statement-blackhawks-statement-on-name-and-logo/c-317688782.

[21] “Blackhawks Statue Outside of United Center Vandalized Over Weekend, Team Says,” NBC Chicago, accessed November 16, 2020, https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/sports/chicago-hockey/blackhawks-statue-outside-of-united-center-spray-painted-vandalized/2352999/.

[22] NBC Chicago, “Blackhawks Statue”.

[23] Copyright Twitter user @zhigaagoong, https://twitter.com/zhigaagoong/status/1315560484188434432/photo/1.

[24] “Blackhawks Statue Outside of United Center Vandalized Over Weekend, Team Says,” NBC Chicago, accessed November 16, 2020, https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/sports/chicago-hockey/blackhawks-statue-outside-of-united-center-spray-painted-vandalized/2352999/.