Written by: Mikey Spehn

2020 generated a great discussion of history in the public sphere. Following George Floyd’s murder on May 5 of 2020, Black Lives Matter protests worldwide brought systematic racism to the forefront of public and political debate. Historical monuments in America became a target for removal or defacement on a scale usually only seen in a government’s overthrow. In Grant Park, Chicago’s Christopher Columbus statue was the target of vandalization and a confrontation between protesters and police. On July 24, 2020, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot ordered the statue’s temporary removal [2]. How come the same fate has not transpired to the Balbo monument, only a mile south of the monument? Both are equally problematic.

You might be thinking, what is the Balbo monument? The monument is a column from the ancient Roman town of Ostia “that is approximately 2,000 years old dating from between 117 and 38 BC” [3]. The column was given by Benito Mussolini for the Chicago World’s Fair, 1933 Century of Progress.

Mussolini dedicated the column in honor of Fascist General Italo Balbo’s famous transatlantic flight to Chicago for the fair. The column placed in Burnham Park became known as the Balbo monument in honor of the Italian aviator. While in Chicago, Italo Balbo also unveiled the Christopher Columbus statue that toppled in 2020. Both monuments reflect America’s good relationship with a fascist Italy that was controversial even before WWII. So, how has one monument been removed, and another is outside Soldier Field to this day? What is it about Balbo?

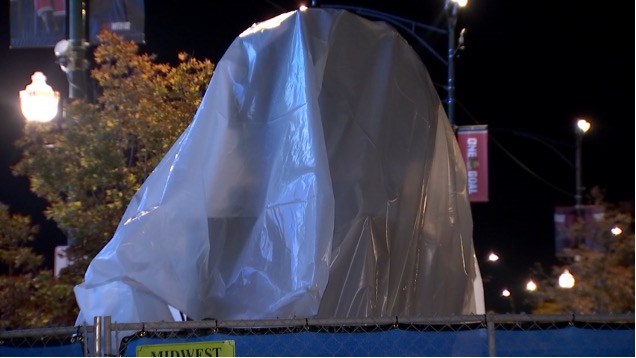

Christopher Columbus’ stone face does not look over Chicago’s landscape anymore. Oddly enough, the base still stands (shown below in image [6]). On the pedestal, there is a commemoration which reads:

“THIS MONVMENT HAS SEEN THE GLORY OF THE WINGS OF ITALY LED BY ITALO BALBO JULY 15 1933.” [2]

The Grant Park monument was under attack by protesters not because of Balbo, Mussolini, or Fascist Italy. Columbus is the pinnacle of white colonialism and is a person of celebration every October in America. It is difficult not to envision the commemoration of Columbus as state-sponsored encouragement of colonialism and racism. A poll has found that 35% of voters in the 2020 election “favor eliminating Columbus Day as a national holiday” [7]. The story is well known to Americans; the history of Mussolini, Balbo, and fascism is not common knowledge. Fascism’s pedestal remains. Columbus has fallen.

Does the pedestal with an inscription for Balbo staying in Grant Park indicate that the Balbo monument will not plummet? It seems so. Even the Columbus statue was only ‘temporarily’ removed by Lori Lightfoot. Chicagoans will see if the removal is actually temporary.

Americans are well aware of systematic racism and the countries past of slavery. But the history of fascism in America is going largely unnoticed. Do Americans know there was an American Nazi Party and that Charles Lindbergh possessed pro-fascist sympathies? The Balbo monument commemorates Italian fascism and an aviator who is known for more than flying. What is it about trans-Atlantic aviators and attraction to fascism? Who’s next, Amelia Earhart?

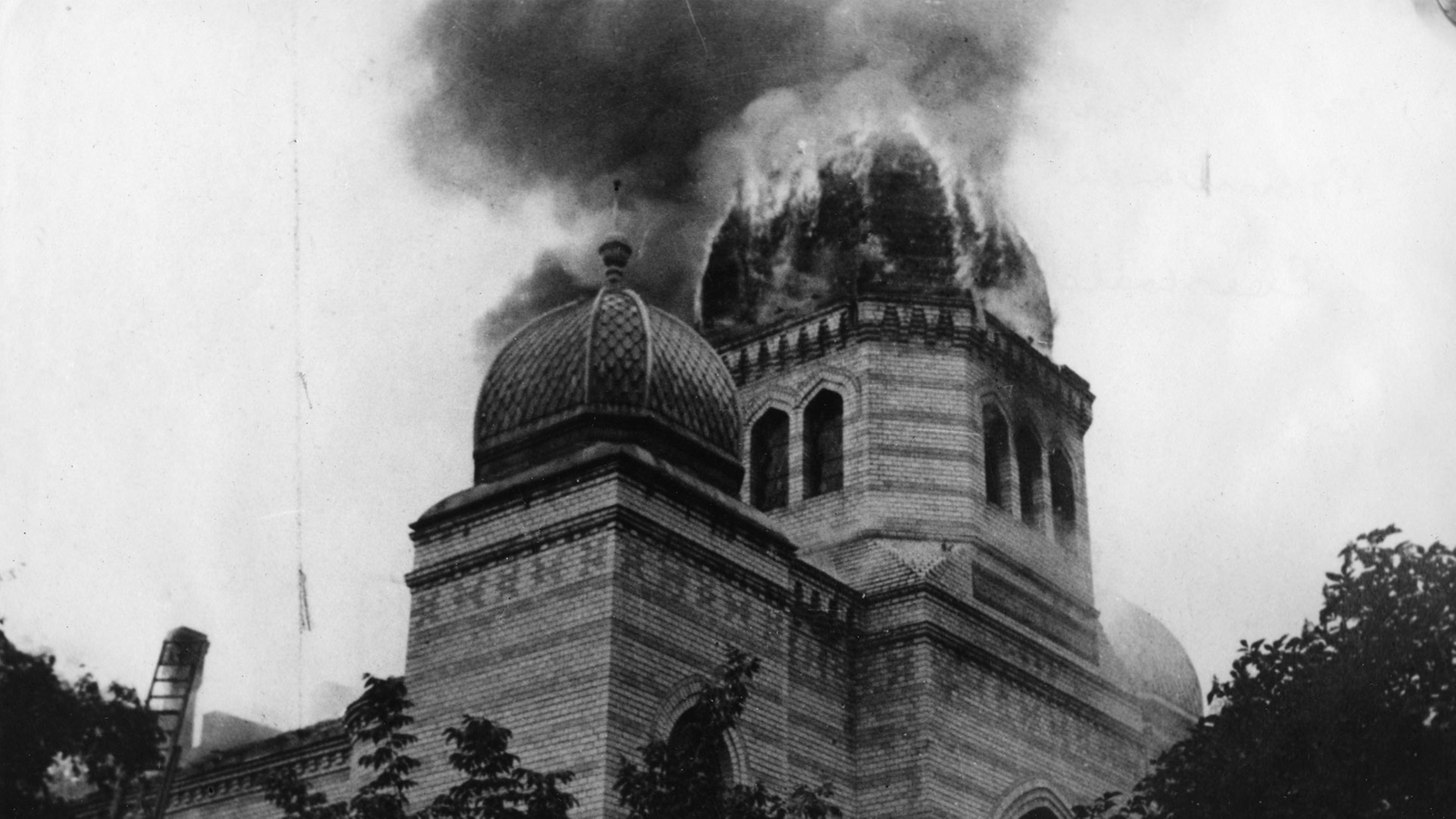

Italo Balbo is not just a supporter of fascism too. Loyola University Chicago professor Anthony Cardoza said, “Balbo was one of the most violent warlords of the Fascist movement and had a pivotal role in bringing Benito Mussolini to power” [8]. He was governor of the Italian colony of Libya and “ordered Jews who closed their businesses on the Sabbath to be whipped” [9].

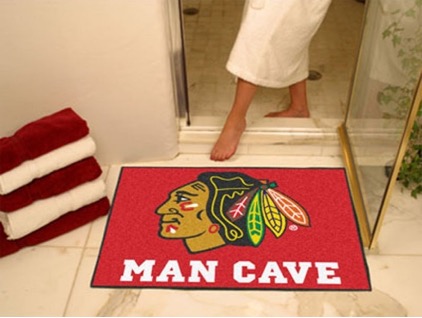

No one doubts that Italo Balbo was a fascist and committed heinous crimes in Italy. So who wants this monument to stay in Chicago? When there were protests to remove the memorial in 2017 (see image [1]), the Joint Civic Committee of Italian Americans (JCCIA) opposed the removal of the column. Supporters of preserving the monument argue that Balbo was a hero who was not antisemitic and was opposed to Nazi Germany. Historians like Anthony Cardoza disagree. But for the sake of argument, let us say Balbo was these things. That still means he is responsible for persecuting Jewish people [9] and “oversaw the use of saturation bombing, poison gas, and concentration camps against indigenous people in Libya and Ethiopia” [11]. A man pictured having niceties with Adolf Hitler is also pictured greeting Chicago Mayor Kelly in 1933. Chicago symbolically still welcomes Balbo in 2020.

Will the Balbo monument come down? Not anytime soon. In 2017, when protests about Balbo were the highest, protesters could not pressure the city to rename the street: Balbo Drive, which is a lot cheaper than removing a statue. Italian American groups don’t want a Roman column taken down. The city does not want to admit there is a problem or pay for a fix. But, most of all, Americans are not ready to confront the country’s fascist past, or at the very least pay for removal of it. Columbus’s downfall is a step in the right direction and confronts America’s systemic racism. Maybe America can only handle processing one historical sin at a time. No one can find a public monument to Italo Balbo in Italy [8]. Others have confronted Balbo’s historical memory in museums and history books. Chicago celebrates his memory with a street name, a monument, and a pedestal without a man above it. Columbus is no longer on a pedestal. Now it is time to protest the man that was below him.

Mikey Spehn, Loyola University Chicago

[1] Briscoe, Tony. “Anti-Fascist Protesters Want Balbo Monument in Chicago Removed.” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 2017. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-balbo-monument-protest-chicago-0824-20170823-story.html

[2] Silber, Christopher. “Columbus Statue’s Turbulent History Included State Funds, Design Feuds, Mussolini Message.” Book Club Chicago, July 24, 2020. https://blockclubchicago.org/2020/07/24/columbus-statues-turbulent-history-included-state-funds-design-feuds-mussolini-message/

[3] “Balbo Monument.” Chicago Park District, 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20160328212825/http://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/burnham-park/balbo-monument/

[4] Mondadori. Edward Joseph Kelly with Italo Balbo, July 1933, Getty Images, accessed November 22, 2020. https://www.gettyimages.ie/detail/news-photo/the-mayor-of-chicago-edward-joseph-kelly-giving-the-keys-of-news-photo/154068760?language=fr

[5] BPK, BERLIN/BAYERISCHE STAATSBIBLIOTHEK MÜNCHEN ABTLG. KARTEN U. BILDER/HEINRICH HOFFMANN/ART RESOURCE, NY, accessed November 22, 2020. https://erenow.net/modern/the-devils-chessboard-allen-dulles-the-cia/26.php

[6] Conkis, James. “Base of Christopher Columbus after its removal on July 24, 2020.” Wikipedia, accessed November 22, 2020.

[7] Sheffield, Carrie. “In heightened cancel culture, most voters still want Columbus Day as national holiday, poll finds.” Just The News, June 26, 2020.

[8] Ackman, Scott, and Schwarz, Christopher. “The (Failed) 1946 Fight to Remove a

Fascist’s Name from a Chicago Street.” Chicago Magazine, July 10, 2008. https://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/August-2008/Dubious-Legacy/#:~:text=In%20August%201938%2C%20Balbo%20visited,down%20his%20plane%20over%20Libya.

[9] Sarfatti, Michele. “The Jews in Mussolini’s Italy: from equality to persecution.” Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 102.

[10] Haberman, Irving. Getty Images. https://www.esquire.com/uk/culture/tv/a33293436/charles-lindbergh-nazi-true-story-the-plot-against-america/

[11] Greenfield, John. “Monument to fascist Balbo likely to remain, but aldermen could still rename street.” Chicago Reader, April 23, 2018.

https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/balbo-monument/Content?oid=46044522

#/media/File:Columbus_Statue_Removal_Grant_Park_Chicago_July_25_2020-2069.jpg)