Have you been at the Western Brown Line Station and noticed a large slab of concrete standing near the entrance? Well this 3-ton piece of rock was once a part of the Berlin Wall [1]. The city of Chicago was offered a piece of the wall by the Berlin government back in 2008 [2]. This donation symbolizes a gesture of gratitude towards the United States for helping secure the freedom of Berlin and the reunification process. While this gesture of goodwill is much appreciated, some may wonder why it was placed in a CTA station. Like so many other important historical artifacts, perhaps the wall should be kept at a museum or even a public library. However, the city decided to place it in Lincoln Square, a historically German neighborhood. Today, we’ll be looking at the history of Lincoln Square and why the Berlin Wall was placed there.

Lincoln Square saw its first settlers as far back as 1850 [3]. A majority of the settlers were farmers from Switzerland, Germany, and England. They would grow their produce and drive along Little Fort Road (Lincoln Ave.) to the market in Chicago. With Little Fort being a high traffic area, shops began to appear along the road. It wasn’t long until investors started building up the area and promoting it for commercial use. The area soon grew in popularity and saw tremendous growth in the early 1900s [4]. In 1907 the first elevated train made its way to Lincoln Square [5]. With the new train came even more residents and immigrants to the area. Over time, Lincoln Square was transformed from a small farming town to a thriving metropolitan area. And finally, in 1920 the town was annexed and became a part of the city of Chicago [6].

During the large influx of immigration, numerous German families moved to Lincoln Square. When the town saw an increase in businesses they were primarily German-owned and operated. This encouraged even more German immigrants to move to the area. It is no surprise that German immigrants would want to move where there was a high concentration of German-Americans. Not only were they able to speak their language among their people, but they were able to shop for the items they used back home. Thus, over the years Lincoln Square earned the reputation as a historically German area. Even as the demographics of the area changed and became more diverse, the city promoted an “Old World flavor with European-style shops” [7]. Lastly, there are multiple German-American events that take place in Lincoln Park. The most famous and popular event that takes place is the German-American Oktoberfest. For one weekend in September, Chicagoans and visitors alike gather in Lincoln Square to celebrate everything German. The goal of the festival is to celebrate German heritage and help keep old traditions and culture alive. From this example it is clear to see just how prevalent German-American history and culture remains in Lincoln Square today. So when it came to the Berlin Wall being put on display, it seemed like the natural choice to place it in Lincoln Square.

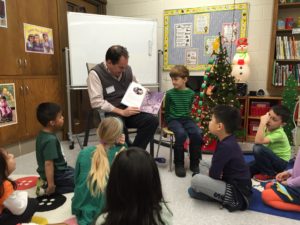

While this explains why the wall is in Lincoln Square, it does not answer why it was placed in the CTA. In 2009, the former Alderman of Lincoln Square, Gene Schulter, was interviewed by the McCormick Freedom Museum. The Alderman explained how he wanted it to be put in a prominent area so that it could inspire future generations. Not only would the monument help kids to understand the importance of the Berlin Wall but also teach them why it should never happen again. In the end, the Berlin Wall Monument is “a celebration of the true meaning of unity and liberty” [8]. Also, the citizens of Lincoln Square were thrilled to have the monument installed in the station. When an important monument, such as this one, is placed in a public area, it feels more accessible to the residents. As the Alderman puts it, having the wall in a public space demonstrates the more human side of it and how the Berlin Wall continues to affect people’s lives.

This is not the only piece of the wall that was placed in a public area. Ever since its fall in 1989, the Berlin government has divided up the pieces to be donated to countries and cities around the world [9]. As of 2020, the Berlin Wall resides in over 40 different countries [10]. These pieces can be found in museums, libraries, businesses, parks, and even schools. Locations include the Berlin Park in Madrid, the Berlin Plaza in Seoul, and the campus of Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. In this way, the question of why the Berlin Wall is placed on the CTA changes to a question of why not? The Berlin Wall has always been about the people. While it was initially meant to divide the Communist East Berlin from the Democratic West Berlin, it has come to symbolize much more. This symbol of hatred has been re-imagined as its worst fears, a symbol of hope, liberty, and freedom.

building to the park’s right. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berlin_Wall_piece_in_New_York.JPG. Gaurav1146, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

To this day, there continue to be celebrations of the collapse of the Berlin Wall and what it means to the city of Chicago. In 2019, the Dank Haus German American Cultural Center hosted a celebration for the 30th Anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s dismantling [11]. The celebration took place at the Berlin Wall Monument for a rededication ceremony. Speakers included Consul General Wolfang Mössinger from Germany and Dank Haus President Dagmar Freiberger. Once the ceremony concluded guests were invited to share their stories about the events leading up to and eventual collapse of the Berlin Wall. This dedication and remembrance demonstrate the significance the wall has today and why it continues to be important to the city of Chicago.

If you haven’t seen the wall, you can visit it at 4648 N. Western Ave, the Western Brown Line CTA Station in Lincoln Square.

Jen Cimmarusti, Loyola University Chicago

[1] McCormick Freedom, “Berlin Wall in Chicago,” produced by the McCormick Freedom Museum, November 9, 2009, accessed November 22, 2020.

[2] B, Mona,“A Piece of Berlin in Lincoln Square,” Lincoln Square Ravenswood Chamber of Commerce (LSRCC), May 28, 2012, https://lincolnsquarecc.wordpress.com/2012/05/28/berlin-in-lincoln-square/. Accessed November 22, 2020.

[3] “Cultural Information,” Lincoln Square Ravenswood Chamber of Commerce, http://lincolnsquare.org/cultural-information/. Accessed November 22, 2020.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Seligman, Amanda, “Lincoln Square,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/747.html/. Accessed November 22, 2020.

[8] McCormick Freedom, “Berlin Wall in Chicago.”

[9] Ziv, Stav, “Where in the World Is the Berlin Wall?” Newsweek, November 11, 2014, https://www.newsweek.com/where-world-berlin-wall-283566. Accessed November 22, 2020.

[10] Hernandez, Alex V, “30th Anniversary of Berlin Wall’s Demise to Be Celebrated At Monument In Lincoln Square,” November 1, 2019, https://blockclubchicago.org/2019/11/01/30th-anniversary-of-berlin-walls-demise-to-be-celebrated-at-monument-in-lincoln-square/. Accessed November 22, 2020.

[11] Hernandez, Alex V, “30th Anniversary of Berlin Wall’s Demise.”

Bibliography

“About Us.” German-American Fest. Accessed November 23, 2020.

B, Mona.“A Piece of Berlin in Lincoln Square.” Lincoln Square Ravenswood Chamber of Commerce. May 28, 2012. https://lincolnsquarecc.wordpress.com/2012/05/28/berlin-in-lincoln-square/. Accessed November 22, 2020.

Chandler, Susan. “A German Flavor Lingers in Lincoln Square.” Chicago Tribune, January 23, 2000. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2000-01-23-0001230342-story.html. Accessed November 22, 2020.

“Cultural Information.” Lincoln Square Ravenswood Chamber of Commerce. http://lincolnsquare.org/cultural-information/. Accessed November 22, 2020.

Hernandez, Alex V. “30th Anniversary of Berlin Wall’s Demise to Be Celebrated At Monument In Lincoln Square.” November 1, 2019. https://blockclubchicago.org/2019/11/01/30th-anniversary-of-berlin-walls-demise-to-be-celebrated-at-monument-in-lincoln-square/. Accessed November 22, 2020.

McCormick Freedom. “Berlin Wall in Chicago.” Produced by the McCormick Freedom Museum. November 9, 2009. Accessed November 22, 2020.

Seligman, Amanda. “Lincoln Square.” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/747.html/. Accessed November 22, 2020.Accessed November 22, 2020.

Ziv, Stav. “Where in the World Is the Berlin Wall?” Newsweek. November 11, 2014. https://www.newsweek.com/where-world-berlin-wall-283566. Accessed November 22, 2020.

Images

“Berlin Wall in Lincoln Square.” Lincoln Square Ravenswood Chamber of Commerce. https://lincolnsquarecc.wordpress.com/2012/05/28/berlin-in-lincoln-square/. Accessed December 6, 2020.

A segment of the Berlin Wall in New York on East 53rd Street between 5th and Madison Avenues in Paley Park, later relocated to the lobby of the building to the park’s right. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berlin_Wall_piece_in_New_York.JPG. Gaurav1146, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Accessed October 17, 2021.