By Maris Rosenfield, Loyola University Chicago

In Chicago’s Lincoln Park, there are many monuments dedicated to significant figures in history. Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin and more stand tall within the expansive park. Among these historical giants stands a monument to John Peter Altgeld, a governor of Illinois who fought for justice reform and pushed his progressive views during his term. Altgeld’s legacy is one of restitution, as he has been described as “the most abused and reviled man of his generation” [1]. His monument may sit humbly in Lincoln Park, but his character and his contributions to society make him a quiet but significant influential player in history.

John Peter Altgeld was born in Germany in 1848. His family traveled to the United States, settling in Mansfield, Ohio when John was three months old. His father worked on a farm, upon which John began to help when he was 12. Despite the workload and his illiterate father’s lack of support, John excelled in school. After various moves westward from Ohio, Altgeld settled in Chicago in 1875. He first focused on real estate by buying lots and building office structures. But his interests in politics and law caught up with him, and he was elected governor of Illinois in 1892.

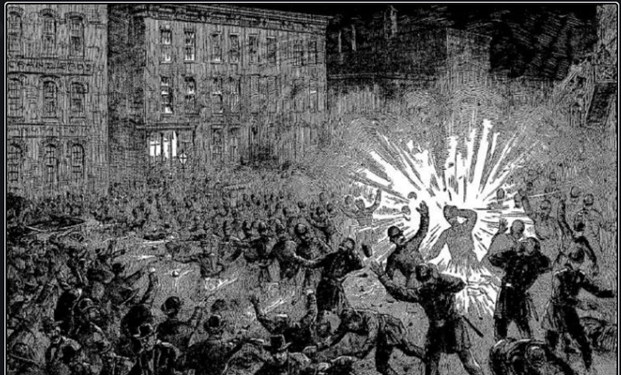

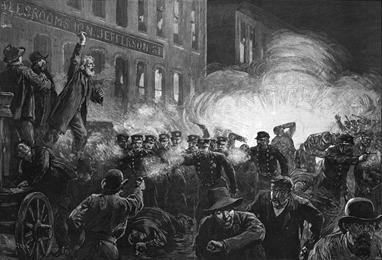

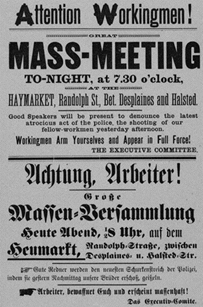

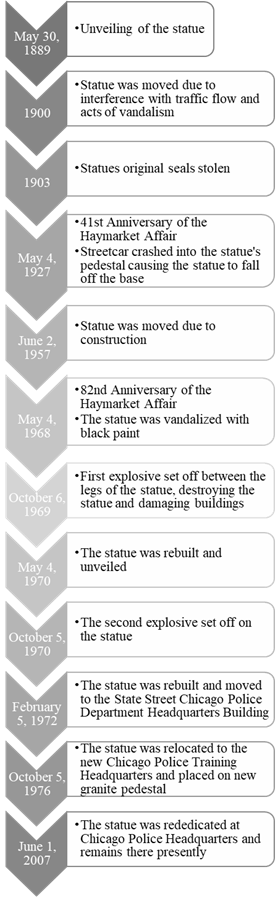

Altgeld made several then-controversial decisions during his governorship, but his boldest move was to pardon the three men still serving time for the infamous Haymarket Affair. On May 4, 1886, a bomb went off at a Chicago labor meeting that resulted in seven policemen and four workmen’s death and seventy others injured. Eight men were accused, arrested, and tried—all eight were found guilty and five were hanged. Seven years later, in 1893, Altgeld pardoned the remaining three men.

The trial was riddled with controversy and injustice. In his pardon, Altgeld insisted that “the jury was not chosen by chance as required by law but from a panel collected personally by a special bailiff who boasted that he had called only those men who ‘he believed would hang the defendants’ ”[1]. Overall, in his 18,000 word pardon, Altgeld argued that the trial was unjust and that the evidence presented could not have rightfully convicted the three remaining defendants [2]. When his party reacted negatively to his decision to pardon, Altgeld is to have said:

“No man…has the right to allow his ambition to stand in the way of the performance of a simple act of justice” [3]

The public did not take kindly to Altgeld’s decision. He, along with the three men pardoned, were deemed “anarchists” by the public and press, with various news outlets denouncing Altgeld and attacking the pardon. The Chicago Tribune went so far as to compare pardoning those involved with the Haymarket Affair to the states that seceded from the Union during the Civil War, writing: “The Chicago Tribune, characteristically a pioneer in such matters, led the outcry. ‘Never’ said its editor, ‘did the Governor of an American State—with the exception of those Southern Governors who issued secession proclamations—put his name to so revolutionary and infamous a document.’ On the next day, the editor, noting the widespread denunciation of Altgeld with satisfaction, remarked that ‘the political remains; of Altgeld would draw the salary of governor for forty-two months longer.” [4]

The decision to pardon the three remaining “anarchists” effectively ruined Altgeld’s political career. While he still had speaking engagements, he was not re-elected as governor nor to any other political office. He died in 1902 at the age of 54 of a cerebral hemorrhage.

For someone vilified by the press and general public, it is hard to imagine why he would have a monument in one of the largest parks in the city. After his death, however, the public opinion of Altgeld began to shift. In 1913, more than a decade after his death, $25,000 was appropriated for a monument to Altgeld. With a design competition to choose the sculptor, the city of Chicago that once tried to destroy Altgeld began to make amends. [5]

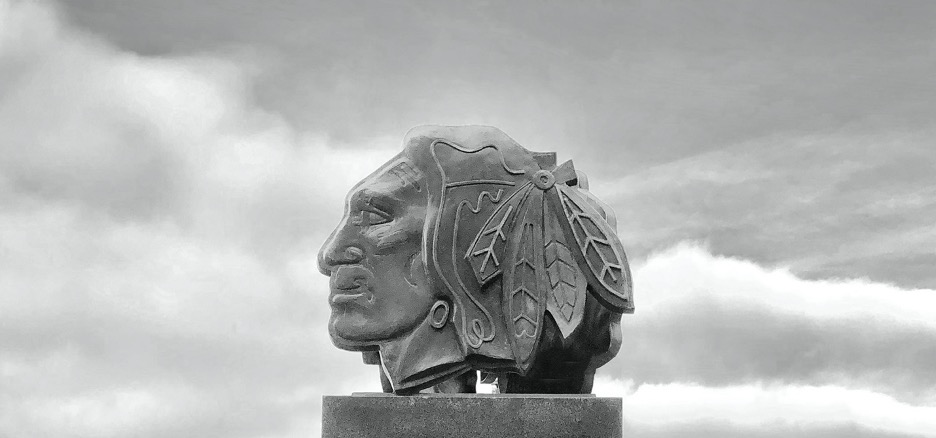

The final monument, designed by Gutzon Borglum, is made of bronze and shows Altgeld standing with a man, woman and child crouched at his side. The figures around Altgeld’s legs seem to represent that he was an advocate for the working class, as well as his upbringing as such. This symbolism is further realized in the fact the monument itself was dedicated on Labor Day in 1915. Altgeld, while known for his pardoning, was also deeply involved in leading “…progressive reforms such as workplace safety and child labor laws” [5]. To unveil this monument on Labor Day was symbolic considering Altgeld’s work while adding to the acknowledgment of all he did for the working class during his legal and political careers.

While this monument may not be the most grand, nor have the most exciting history, it is an excellent example of honoring someone who fought for what he or she thought was right despite popular opinion. It is often the case that monuments have controversy surrounding them, as with the Confederate statues in the South, or even the Balbo Monument here in Chicago. But John Peter Altgeld deserves his place in Lincoln Park, as he represents morality and dignity even when it seems the world is against you. The monument to Altgeld is one of the only remnants of his legacy, which is a shame. He is often left out of the historical narrative, as it has been written:

“Altgeld in history books is usually one of the unusual statesman of America who was attacked by big corporations and promoted interests of farmers and workers and gave ‘an outstandingly able, courageous, and progressive administration’. Even a book claiming to provide ‘essential facts of her political life’ and insisting that America was different because it was populated by people ‘who believed in restricting oppression rather than submitting to it’ mentions Altgeld only marginally, though it is established fact of history that Altgeld stood for rule of law and sacrificed almost everything for not submitting to injustice and oppression.” [6].

The next time you stroll through Lincoln Park, be sure to stop by and see this shred of the legacy of John Peter Altgeld. His perseverance in the fight against injustice, especially to the working class, makes him worthy of his bronze statue.

[1]Madison, Charles A. “John Peter Altgeld: Pioneer Progressive.” The Antioch Review 5 (1945): 121–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4609065.

[2]Parsons, Albert R. Gov. John P. Altgeld’s Pardon of the Anarchists and His Masterly Review of the Haymarket Riot . Chicago, IL: Lucy E. Parsons, 0AD. http://moses.law.umn.edu/darrow/documents/Altgeld%20pardon%20lucy%20parson.pdf.

[3]Sampson, Robert D. “Governor John Peter Altgeld Pardons the Haymarket Prisoners.” Illinois Labor History Society. Illinois Labor History Society, January 23, 2016. http://www.illinoislaborhistory.org/labor-history-articles/governor-john-peter-altgeld-pardons-the-haymarket-prisoners.

[4]Wish, Harvey. “Governor Altgeld Pardons the Anarchists.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 31 (1938): 424–48. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40187873.

[5]District, Chicago Park. “John Peter Altgeld Monument.” Chicago Park District. Accessed November 2020. https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks-facilities/john-peter-altgeld-monument.

[6]Varma, L.B. “History and Historical Fiction: A Study of Howard Fast’s ‘The American’.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 48 (1987). https://www.jstor.org/stable/44141779.

Adelman, William J. “The Haymarket Affair.” Illinois Labor History Society. Accessed November 2020. http://www.illinoislaborhistory.org/the-haymarket-affair.

Busch, Francis X. “The Haymarket Riot and the Trial of the Anarchists.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 48 (1955): 247–70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40187873.

Paretsky, Sara. “John Peter Altgeld.” Statue Stories Chicago : John Peter Altgeld. Accessed November 2020. http://www.statuestorieschicago.com/statues/statue-altgeld/.

#/media/File:Columbus_Statue_Removal_Grant_Park_Chicago_July_25_2020-2069.jpg)